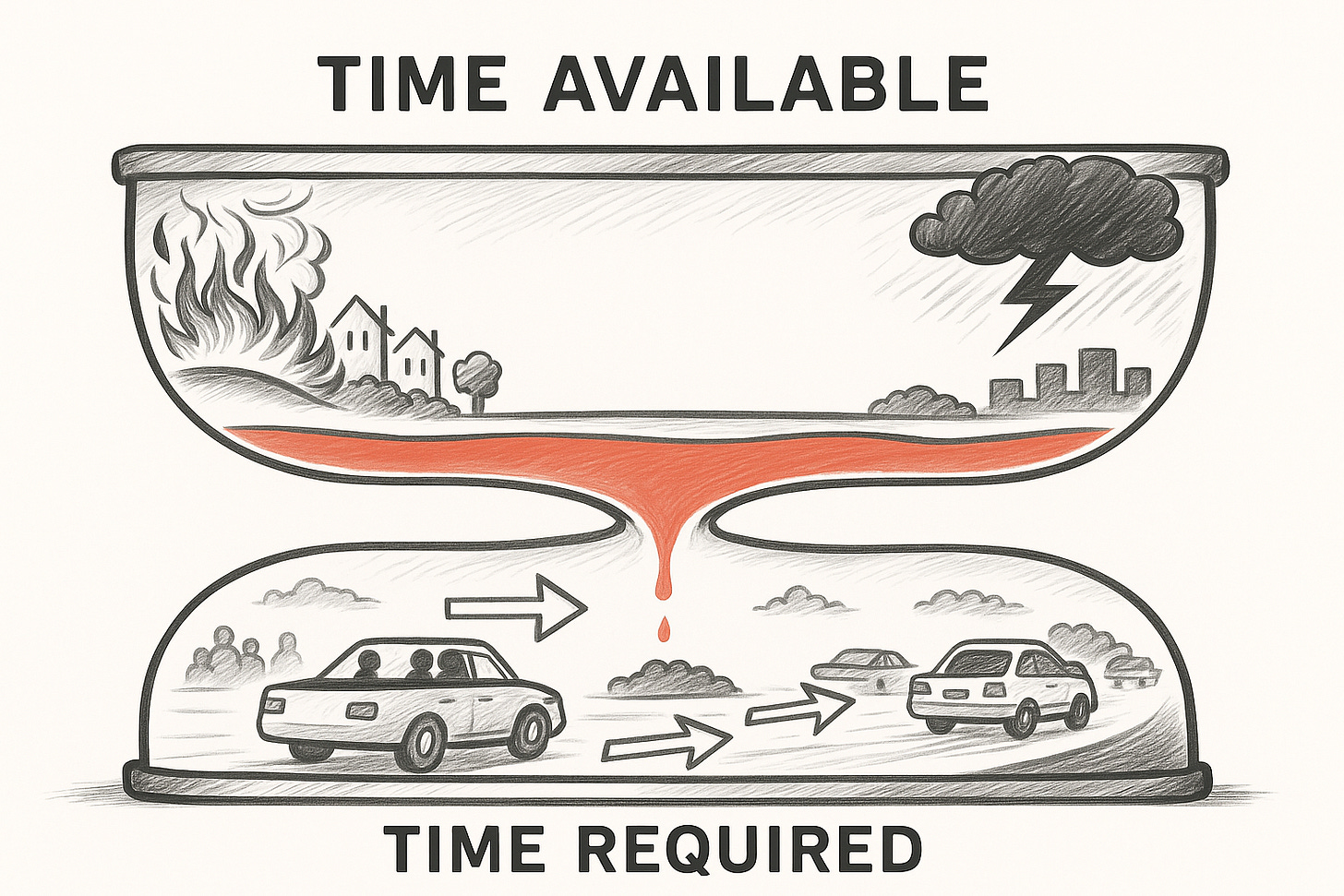

Evacuation: The Race Between Time Available and Time Required

How Public Safety Can Buy Time Before the Crisis Begins

At its core, every evacuation hinges on a single, straightforward question: do we have enough time to complete the process?

Evacuation planning is a constant race between the time available and the time required to move people safely out of harm’s way. That balance determines whether an evacuation unfolds in a proactive, orderly manner—or devolves into chaos and reactivity. When there’s less time available than the time required, people get trapped, plans break down, and responders are forced to make impossible decisions.

Understanding Time Available

The time available to evacuate is largely dictated by the hazard itself.

In a wildfire, it’s the time between ignition and impact as the fire travels toward populated areas.

In a dam failure, it’s the brief window between the first breach and when floodwaters arrive at destructive levels.

While those timelines are often set by nature, communities can influence them.

Hazard mitigation measures—fuel reduction, defensible space, and strengthened infrastructure—can slow the rate of escalation and increase the time available.

Rapid first responder actions during the initial attack of a wildfire or action to an an evolving threat of violence can extend that window, buying critical minutes or hours for evacuation decisions and public warning.

The goal is simple: stretch the time available as far as possible before an incident makes movement mandatory.

Understanding Time Required

The time required, however, is something we can directly influence. It’s the cumulative total time of every step, decision, and communication between the first detection of danger and the final vehicle clearing the evacuation zone.

There is time required:

To detect the incident and spot a new wildfire, learn of a hazardous materials release, or recognize river and stream banks overflowing.

To dispatch responders and for them to build situational awareness once on scene.

To translate that assessment into decisions about whether an evacuation is needed and to communicate those decisions to whoever is responsible for public alerting.

To develop the alert and warning messages, have them approved, and issue them to the public.

For residents to receive the alert, make sense of it, decide what to do, and begin moving.

To finally execute the evacuation itself—coordinating the movement of everyone willing to evacuate from dangerous areas to safe ones.

Each of these steps consumes precious time, yet each can be shortened through situational awareness, planning, coordination, and training.

The goal of an evacuation plan, then, is to reduce the time required wherever possible. Through pre-planning, refined alert and warning processes, pre-positioned resources, and well-rehearsed traffic management procedures, communities can shave minutes off each phase of response. Every minute gained in readiness is a minute returned to safety.

For more evacuation-focused resources, check out our growing list of articles, case studies, and tools designed to improve how agencies prepare for incidents that require evacuating the community.

The time required to physically clear an area is shaped by both measurable factors, such as traffic volume, as well as unpredictable ones like human behavior and environmental damage.

Evacuation clearance times depend on how many people are moving, how many vehicles they use, and the capacity of the roads that serve them. Tools can model these dynamics, estimating how long it will take to clear a community.

Models can’t account for the human element: stress, uncertainty, and fear that slow decision-making and driving; stalled vehicles that clog lanes; or visibility reduced by smoke, debris, or rain.

And they can’t capture cascading impacts: fallen trees, downed power lines, flooded roadways, or blocked intersections that alter evacuation routes in real time.

That’s where planning stops and leadership begins. The agencies that invest in coordination, communication, and pre-staged response can transform those minutes of friction into moments of readiness.

Buying Time Through Situational Awareness

One of the most effective ways to increase the time available and decrease the time required is by developing pre-incident awareness. When public safety agencies develop and share information about dangerous conditions before an incident begins, they buy time not only for themselves but for the public.

We saw this in Los Angeles in the days leading up to the January 2025 fires.

Public messaging about potential fire conditions—issued before any ignition occurred—gave residents a chance to prepare vehicles, review routes, and make mental decisions about when they’d go if needed.

With improved situational awareness and advanced notice, agencies can:

Rehearse their evacuation plan and review the process for adjusting traffic signal timing.

Pre-stage barriers and signage for rapid road closures.

Coordinate staffing policy changes, leadership responsibilities, and daily routines.

Position supervisors and patrol units at key intersections before the public starts to move.

These actions can prevent or facilitate a rapid response to the backups, bottlenecks, and collisions that often occur once evacuation orders are issued. They transform minutes of chaos into minutes of control.

Evacuations will always begin under pressure—but improving the situational awareness that precedes them allows organizations to make the most out of every precious second and minute. Through foresight, coordination, and preparation, they can improve the odds that when the incident occurs, the time available exceeds the time required.

Conclusion: The Leadership Imperative

Public safety leaders can’t always control the hazard, but they can control their readiness. They can build the coordination, communication, and capability to ensure that when the next incident begins, the time available exceeds the time required.

Recognizing this dynamic also allows communities and public safety agencies to establish baseline performance metrics for evacuation readiness. Once those baselines exist, agencies can target capability-building efforts to reduce the time required in measurable ways.

For chiefs and command staff, the next step isn’t philosophical, it’s diagnostic. Questions that form the foundation of an operational improvement plan include:

How long does it take for a police officer or supervisor in the field to pass evacuation area information to dispatch or the alerting authority?

How long does it take for dispatchers to convert that information from a radio transmission or text message into an actionable public alert?

How long does it take for traffic management leadership to adjust signals to facilitate outbound flow?

How long does it take a supervisor to establish a traffic management plan and deploy officers to key intersections?

The list goes on, but agencies that know their numbers can improve them. The agencies that measure performance before the incident are the ones that are prepared to move faster when it matters most.

With every evacuation, the race between the time available and the time required is being run. The only question is, will your organization’s foresight, leadership, and disciplined preparation have put your community into a position where it can succeed and accomplish your evacuation objectives? Or, will you be left scrambling because foundational evacuation concepts were never developed and honed?

Because when the next evacuation begins, the only question that will matter is the same one we started with: do we have enough time?

Enjoyed This Article? Pass It On.

If this article sparked ideas, share it with your network, a colleague, or on social media. Sharing is how we expand the community of professionals committed to staying left of bang.

Great article with very useful information. 👍