Hill Climbing, Acting on Warnings, Middle Management & More

Profiles in Preparedness #44

Welcome back to The CP Journal, where we break down what it takes to get left of bang.

There’s a difference between a general warning and a specific one.

A general warning is when you learn about something that might affect your organization, your community, or your family—but you don’t know when, where, or how it will manifest.

A specific warning has those details: time, location, and impact. It’s the prompt that starts the clock and is the moment response begins.

The problem is that we live in an age where every general warning gets treated as if it were specific. This creates two challenges for professionals working to protect and prepare their organizations.

First, because the loudest voices are often the least credible—people eager to spread alarm for attention or money—they create noise that buries the signal. They’re easy to dismiss, but they make it harder for the professionals who are quietly collecting information, analyzing trends, and issuing credible early warnings.

Their fear-based messages drives attention, but not the accuracy needed to act. Yet the generalized alarmists are always the first to shout, “I told you so!” when something happens, which leads to the second challenge.

The second challenge is that you can’t stop what you’re doing and focus all of your attention on the threat or hazard headlining the day. Mistaking the urgent for the important means you won’t make meaningful progress on anything.

While Noah nailed his ark-building project, for every Noah who built early, there are dozens of organizations that built late or built the wrong thing altogether. Projects that fail to produce meaningful outcomes, or don’t strengthen the organization in the process, create resistance informed by broken trust and wasted resources. The next time a credible threat emerges, leaders hesitate. They tune it out. And by the time the warning becomes specific, the time to act is gone.

It’s also worth remembering that general warnings aren’t always about threats—they can also foreshadow opportunity. The same patterns that hint at instability can reveal emerging markets, shifts in behavior, or unmet needs. Those who only see risk miss the upside available to those who prepare for change instead of fearing it.

So how do you navigate that uncertainty without overreacting or ignoring it altogether?

Curate your inputs and broaden your view. Trust sources that show their work. If you don’t know how they gather or verify information, your ability to rely on it is limited. Your perception of risk is shaped by what you pay attention to. Seek out information that challenges your assumptions, not just reinforces them. It’s how you spot weak signals early.

Have a process to select your projects. Assess threats and hazards systematically. Determine which warnings deserve focused attention and which can be addressed through existing preparedness work. Without a process, you risk chasing noise instead of building readiness.

Build low-regret responses. Take general warnings seriously without overcommitting every time a new “threat” trends online. You’ll get some assessments wrong—acknowledge that and stay positioned to adapt. Establish pre-event indicators that help you recognize when a general warning is becoming specific.

Preparedness, whether personal or organizational, is about making decisions before certainty exists. It forces a balance between preparing for what could happen and what will happen.

While much of training and education focuses on what to do and how to do it, the real differentiator is knowing when to act.

That discernment—knowing when to turn foresight into action—is the mark of an experienced leader.

Inside The CP Journal

Here is an article that was added to the site this week.

Operational leaders face a constant challenge when preparing their organizations and teams for an uncertain future: the effort often depends on the support and buy-in of senior executives and peers. Unfortunately, sometimes this support only comes when something has gone wrong.

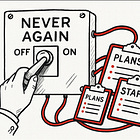

🔒For Paying Subscribers: This article looks at ways to get left of bang to the next disaster, disruption, or crisis, the minute an executive says, “We can’t let that happen again.”

This Week‘s Reads

Here are a few standout reads from this week with insights, ideas, and perspectives that caught my attention.

Article | Hill-Making vs Hill-Climbing. Are you relentlessly optimizing what you already do, or are you exploring new areas to master? This article from Kevin Kelly addresses a tension I’ve faced throughout my career and one that’s directly relevant to people and organizations working to get left of bang. It explores the strategies, risks, and opportunities that come with each approach to growth.

Article | The Case for Middle Management. In the 1990s, Jack Welch popularized the need to “de-layer” and flatten organizations—a concept AI is championing today. This article from the McChrystal Group takes a different perspective, positioning middle management as a critical layer that actually enables the change organizations want. If you’re an executive, this article is worth reading as you consider your ownership of the problem and the systemic challenges that prevent middle management from meeting that goal.

Enjoyed This Issue? Pass It On and Go Deeper.

If this newsletter sparked ideas or challenged your thinking, share it with your network, a colleague, or on social media. Sharing is how we expand the community of professionals committed to getting and staying left of bang.

And if you want to go further, become a paying subscriber for exclusive access to:

The Tactical Analysis Course & behavioral analysis practice exercises

The Project Management in Emergency Management Playbook

The Operational Readiness Playbook that details how to build a watch office

And if you’re thinking about how to strengthen your organization’s preparedness, that’s what we do. Whether it’s strategy development, assessments, planning, speaking events, or exercises, we help teams build the skills and strategies to stay ahead of the next challenge.