Integrating Crisis Management and Business Continuity at Airports

Four Research-Backed Takeaways Every Operations Leader Should Know

Introduction

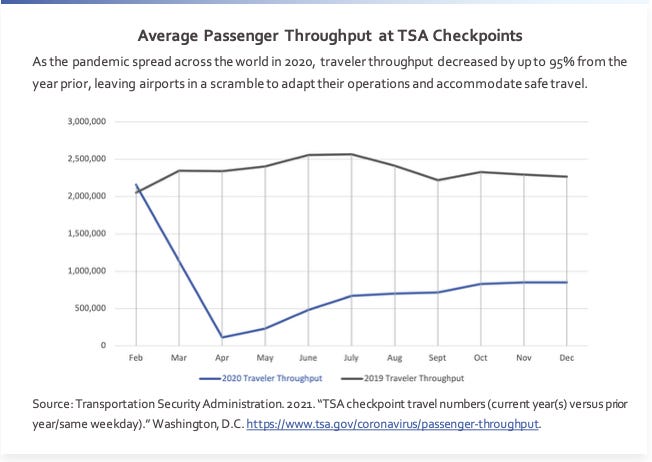

In early 2020, the aviation industry faced a collapse unlike anything in its history. Passenger throughput at TSA checkpoints—a barometer of air travel demand—dropped by as much as 95% from the prior year, leaving airports scrambling to adapt operations, manage safety concerns, and keep essential functions running.

The COVID-19 pandemic was an extraordinary crisis, but it was also a stress test. It revealed how unprepared many organizations were to simultaneously manage an incident and its cascading impacts on operations. And while the pandemic is now more than five years in the past, the challenges it exposed are anything but over.

Recent events—such as the massive CrowdStrike outage that sparked global travel chaos, the escalating threat of terminal violence at hubs like O’Hare and Sydney, and the accelerating impact of severe weather at airports—show that the next disruption is never far away. Airports now face an evolving risk landscape shaped by rising energy demands, a changing climate, geopolitical uncertainty, and accelerating technology risks. In an interconnected industry, a disruption at one airport can quickly create impacts felt across regions, sectors, and even continents.

From the fall of 2020 through the spring of 2022, I had the privilege of leading a multidisciplinary research team of emergency managers, airport operators, and industry experts to address this very problem. Our work—conducted for the Airport Cooperative Research Program (ACRP), which is part of the National Academies of Sciences and the Transportation Research Board—produced ARCP Research Report 268: Integrating Crisis Management and Business Continuity at Airports - A Practical Guide.

Because the project unfolded during the pandemic, our insights weren’t academic hypotheticals. We learned in near real time from airports wrestling with these challenges, giving us a unique opportunity to see both their successes and their setbacks as they unfolded.

In this article, I’ll share four takeaways from the research—along with how these lessons have evolved in the years since.

Takeaway #1: The Case for Integration

If there’s one theme that emerged above all others, it’s this: crisis management and continuity can’t be treated as separate, sequential efforts. In too many organizations, continuity is viewed as a “recovery” activity that begins only after the immediate crisis is resolved. That mindset and approach waste precious time.

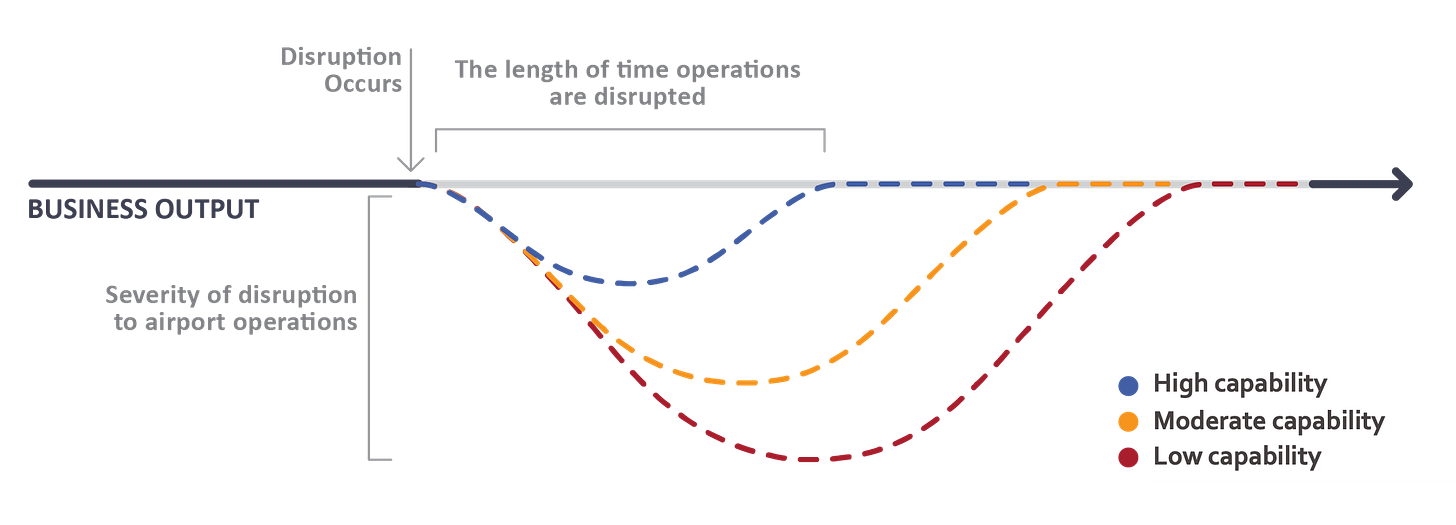

Figure: High-capability organizations recover faster and with less severe impacts than those with low capability.

Continuity is a response phase function—it should begin the moment a disruption is recognized, if not before. When integrated into crisis management from the outset, it delivers tangible benefits:

Shortens the duration and reduces the severity of operational disruptions.

Balances life-safety imperatives with the need to protect business objectives.

Prevents burnout in prolonged incidents by structuring sustainable staffing models rather than relying solely on “all-hands-on-deck” surges.

For operations leaders, the impact is significant. The longer the response drags on, the greater the operational, financial, and reputational costs. Conversely, an integrated approach positions an organization to limit the disruption’s scope, restore essential functions faster, and protect strategic priorities.

Takeaway #2: The Need for Plans…and Their Limits

One of the most striking findings from our research was how often plans were absent from the actual response to COVID-19. More than a few airport leaders admitted they had continuity plans for pandemics sitting on the shelf—some only “rediscovering” them months, or even a year, into the pandemic. Others had plans that were thick, compliance-driven binders, but so impractical that they were never opened once the crisis began.

This wasn’t because planning is unimportant. It was because, in the moment, people defaulted to what they knew, what they had practiced, and the relationships they could leverage—not to an unfamiliar document.

Yet plans are essential. Especially for contingencies that aren’t part of daily operations, a well-designed plan can be the difference between organized action and ad hoc scrambling. The key is that plans must be:

Actionable: providing clear steps that can be implemented under stress, without wading through irrelevant details.

Adaptable: flexible enough to adjust as the situation evolves and new information comes in.

Sustainable: realistic for the resources you have, not just in the first 48 hours, but over days, weeks, or months if the disruption endures.

Where possible, plans should embed familiar, day-to-day practices so that activating them feels like a natural extension of normal operations rather than a wholly separate process.

This is why the ACRP research framed crisis management and continuity capabilities around four essential elements, with each one reinforcing the others to create a practical, integrated program:

Plans: Simple, mission-aligned tools for restoring essential functions.

People & Stakeholders: Engaged networks across departments and partner organizations, ready and able to act.

Resources: Systems to acquire, track, surge, protect, and reallocate critical assets during disruptions and crises.

Training & Exercises: Routine, integrated practice that builds critical thinking and adaptability.

Plans alone won’t carry you through the next disruption—but without them, your capabilities will always have a ceiling. The goal is to use planning as the foundation for building the skills, relationships, and systems that make real-world execution possible.

Takeaway #3: Focus on Impacts, but Monitor for Early Warnings

In crisis management and continuity planning, impacts are often the most visible (and most pressing) concern. A loss of a facility, a staffing shortfall, or a critical resource outage all demand immediate action. But waiting to see those impacts before you act forces you into a purely reactive posture.

The solution is to shift your attention to pre-event indicators—the subtle signs that a threat or hazard is gathering momentum and poses a risk to your operations. By monitoring these indicators, you can prepare your organization for those contingencies and take action before the full impact is felt.

Take the Heathrow Airport power outage on March 21, 2025, as an example. A fire at a nearby electrical substation knocked out power and forced a shutdown affecting over 200,000 passengers. What’s critical is that airlines had flagged concerns days before the incident—including incidents of cable theft that disabled runway lighting. Yet the airport, based on the reports I’ve read, didn’t take proactive action to prepare for a potential disruption in its energy supply. Because the outage had been seen as a “very low probability event” and the airport had paid for a “supposedly resilient” supply, they missed opportunities to reassess the risk and prepare to shift to alternative power sources.

This is the goal of shifting left of bang. You may not be able to prevent every incident, but with early recognition, you can at least prevent being surprised. That means you can pre-position resources, adjust staffing, engage partners, and get ahead of the operational curve.

Bottom line: You care about impacts, but if you’re only watching for them, you’re already behind. Build your monitoring around the indicators that lead to those impacts, and you’ll shift your organization from reactive response to proactive readiness.

Takeaway #4: Your Line of Succession May Make Different Decisions Than You Would

One of my favorite moments from the project—and a tactic I’ve used with many clients since—came during a tabletop exercise where we split participants into two groups. The first group consisted of the principal decision-makers: the senior leaders who normally make strategic and operational decisions during a crisis. The second group was made up of their designated backups: the people who would step into those roles if the principals were unavailable.

Both groups were presented with the same disruption scenario and worked separately. When we compared results, the look on the principals’ faces told the story: their backups made very different decisions.

It wasn’t that either group was right or wrong. But the backups approached the situation with different strategic priorities, goals, and definitions of success. Because those differed from the principals, their tactics, resource allocation, and stakeholder engagement naturally followed a different path.

That difference matters. Preparing alternates for decision-making roles takes time and hands-on exposure during both normal operations and crisis scenarios. Without that preparation, backups will naturally fill in the gaps themselves, and often in ways that don’t align with the broader organizational strategy. In a real event, this can easily pull crisis management and continuity teams out of sync, especially if they’re working in parallel but not toward the same objectives.

The fix is not complicated, but it is deliberate:

Engage executives early to align continuity priorities with strategic goals and ensure those priorities are understood down the line of succession.

Map and prioritize essential functions, and share the reasoning with up-and-coming leaders so they understand the “why” behind decisions.

Build redundancy not only in systems and resources, but in leadership depth.

Integrate continuity objectives into existing crisis exercises so you can test not just the plan, but how successors make decisions under pressure.

Succession planning is more than putting names on a chart. It’s preparing the next person in line to think, decide, and act in a way that keeps the entire organization’s response coordinated—even when the people, resources, and facilities you normally rely on are under strain.

Closing Thoughts

The disruptions airports and other operational organizations face today are more frequent, more complex, and less forgiving than ever before. Whether it’s a global pandemic, a cascading technology failure, a security incident, or an infrastructure outage, the margin for error is thin.

The four takeaways in this article aren’t abstract theory—they come from lessons learned in real time, from real leaders, in real crises. They underscore that:

Continuity must start during the response, not after.

A plan’s value is in how it builds capability.

Early indicators are as important as visible impacts.

Your successors need more than a title—they need the context to lead.

When crisis management and continuity are integrated, organizations can respond faster, sustain operations longer, and return to stability sooner. And that integration doesn’t happen by accident—it’s the product of deliberate preparation, aligned priorities, and leaders willing to think left of bang.

What Comes Next

At The CP Journal, we help operational leaders turn these concepts into tailored, practical programs—from building actionable plans and training your team, to strengthening leadership depth and monitoring for early indicators.

If these takeaways resonate with you:

Subscribe to our updates for more research-backed insights.

Share this article with a colleague who manages critical operations.

Let’s talk about how these takeaways apply in your environment.

Because the next disruption is already on the horizon—and how you prepare now will determine how you perform then.