The Evolution of Left of Bang

Choosing To Be Prepared for What You Can, and Can’t, Prevent From Happening

The Origin Story

When Left of Bang was first published, it introduced a way of thinking shaped in the U.S. Marine Corps’ Combat Hunter program. In that context, “bang” marked the moment an attack occurred—the instant rounds were fired, an IED detonated, or an ambush was sprung. Everything to the left of that moment was time and opportunity; everything to the right was reaction and consequence.

While the book focused on violent acts and was written to empower Marines with the skills needed to prevent attacks1, the principle was never confined to combat. In public safety, business, corporate and cybersecurity, disaster management, healthcare, education, and so many other fields, “bang” is simply the point when the impacts of an event are first felt. It could be the first news alert of a data breach, the moment a hurricane makes landfall, a shot being fired, or the instant a market-shifting announcement hits the wires.

Being left of bang means recognizing the situation before impacts occur—detecting the warning signs and acting while there’s still time to shape the outcome. Being right of bang means recognition comes only after impacts have begun, when options have narrowed and the cost of action has risen.

When we first wrote about this, the focus was personal2 and tactical—spotting the human behaviors that precede violence. Over time, the concept has evolved into a broader framework for organizational readiness. Whether you’re a patrol officer, a corporate leader, a city emergency manager, a nurse, or a teacher the same timeline applies. The further left you can operate, the more options you have and the more influence you can exert over what happens next. The further right you are, the more you’re left reacting—often with less information, fewer resources, and higher stakes.

The Cost of Being Right of Bang

Right of Bang organizations are those that first learn about an event after it’s underway and only then begin their response.

When that happens, there’s a predictable sequence of events that repeats across industries and incident types:

Initial Confusion: People are caught off guard. They scramble, uncertain of what’s needed, what’s already been done, and who’s doing what.

Communications Falter: Every channel—radio, text, phone, chat—gets flooded. Accuracy drops. Noise goes up.

Delayed Activation: Decision-making slows, uncertainty freezes action, and contradictory orders emerge.

Resource Problems: Either people self-deploy without coordination or they stay put because they’re unsure what’s needed. In both cases, resources aren’t where they’re needed when they’re needed.

Crisis Escalation: Secondary incidents and cascading failures compound the original problem.

Lengthy Response and Costly Recovery: Coordination issues extend the incident and drive up recovery costs.

And these aren’t just process problems, they’re cost problems:

Loss of Life: In high-risk events, delays can be deadly.

Financial Impacts: Direct damage, recovery expenses, lawsuits.

Opportunity Costs: Lost chances to mitigate, protect, or capitalize on situations.

Read through enough after-action reviews or post-crisis press coverage, and you’ll see this pattern over and over. Despite truly heroic individual efforts, organizations stuck in this sequence struggle to make the best decisions and position themselves effectively under pressure.

Why Organizations Get Stuck Right of Bang

Sometimes, the reasons organizations are unable to move left of bang are technical or procedural. More often, they’re cultural and political.

Political Risk: Leaders fear the backlash of “overreacting” or “jumping the gun,” so they wait.

Cultural Bias Toward Reaction: Some organizations pride themselves on crisis heroics, equating firefighting with effectiveness.

Institutional Inertia: Plans, processes, budgets, and procurement are built around reacting to known impacts, not detecting emerging threats.

Information Control: Data is siloed or over-filtered before it reaches decision-makers.

Risk Aversion: Waiting for perfect certainty before acting.

Siloed Operations: Departments and agencies don’t share what they know until it’s too late for anyone to act on it.

The result? The organization chooses to operate without its full set of options and pays for it later.

What It Takes to Get Left of Bang

Operating left of bang isn’t about luck. It’s about building the capability to act before the impacts occur. That requires:

Recognizing that events start before impacts occur. Hurricanes form before landfall, attackers prepare before striking, hackers probe before shutting systems down, and businesses recognize a gap before buying from a vendor.

Detecting potential threats or opportunities early. Having the sensors, networks, and awareness to spot changes and indicators before they reach "bang."

Confirming whether those threats and opportunities are real and relevant. Avoiding paralysis by being able to assess and validate threats or opportunities quickly.

Deciding on a course of action before impacts are felt. Establishing triggers, thresholds, and playbooks that guide decisions.

Acting with enough time to influence the outcome. Deploying resources and making moves that change what happens next.

Early recognition triggers every other step. Without it, even the best-laid plans stall.

Getting Left of Bang Today

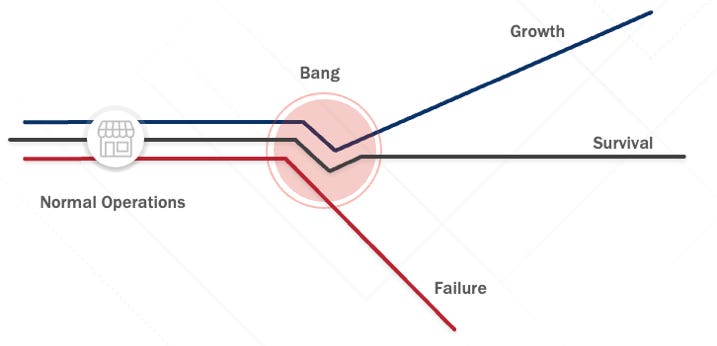

Taken together, these five elements are shaping how organizations position themselves to get left of bang. When bang occurs, whether it’s a threat, disruption, or opportunity, every organization finds itself on one of three trajectories:

Failure: Some organizations are unable to operate when impacts hit. FEMA and SBA data show how many businesses close permanently within days of a disaster. Schools may halt education. Government agencies may be unable to serve their communities in critical moments. In any sector, the inability to function during adversity often ends the mission altogether.

Survival: Others endure the event but struggle. Recovery is slow, adaptation is limited, and the costs are high, whether in staff turnover, burned relationships, or a loss of credibility in leadership. They remain operational, but the setback lingers.

Growth: A smaller group thrives in these conditions. They leverage preparedness, strong relationships, and effective communication to outperform expectations. Growth can be external when companies expand customer bases when competitors falter or government agencies earn trust through visible, reliable service. Or it can be internal when organizations strengthen partnerships, secure resources, and prove their value to leadership.

Every organization is already on one of these lines. That trajectory isn’t set at the moment of bang, but it’s shaped by the choices being made now, the left of bang decisions to build the capabilities to recognize change early and act with confidence before the impacts arrive.

The Path Forward

This is why evolving the concept of Left of Bang remains so important. It’s about using the precious minutes, hours, days, weeks, or months before an event—whether it’s a disruption, an opportunity, or a shift in your operating environment—to build capabilities, develop and pre-position resources, and sharpen your decision-making processes.

Operating left of bang is not a one-time achievement; it’s a discipline. It demands continuous investment in awareness, decision-making, and readiness, because the conditions you prepare for today will not be the same as those you face tomorrow.

What we do now, while still to the left of bang, is what separates organizations that struggle from those that thrive when conditions change. The same principles that help avert a crisis also enable leaders to seize new opportunities, to grow, adapt, and strengthen their position in a shifting environment.

As the world continues to evolve and present new challenges, our approach to readiness must remain proactive, deliberate, and forward-looking.

Get left of bang—and stay there.

The book was written to help deploying Marines recognize threats and take action that could save their life or the lives of squadmates. If just one person was able to get left of bang, that would have been a success. Today, more than ten years after its publication, we are humbled beyond words to continue hearing stories from military members, police officers, security professionals, and others about how something from the book helped save their lives. The book was written for you.

When the Combat Hunter program was first created, the resources, technology, and courses focused on proactive approaches and violence prevention weren’t available. The book and the course have been described as doing the security equivalent of breaking the four-minute mile. Through the case study of the Marine Corps, many organizations now see that violence prevention is possible, and it is encouraging and exciting to see the innovation that is occurring to protect our communities. At the same time, we haven’t done enough. There continue to be attacks in our nation’s schools, ambushes on our law enforcement officers, and violence in public that puts people at risk. This remains unacceptable, and we must continue to find ways to bring this risk to zero.

Thanks for sharing this article, Patrick. After reading your book I was inspired to align your work with mine in the Nursing Home realm. So many of your concepts resonate in this field and we are in need of a change. Things that stand out:

1. Being Proactive. Due to staffing, increased regulations and a changing nursing home population, many facilities find themselves constantly putting out fires and reacting. We just never seem to have the means to get in front of the Bang. Your concepts have reshaped that thinking. By diving into discussions in nursing facilities about situational awareness and prevention, things look completely different. We are using tools (such as our Facility assessments) differently and analyzing weak points. Our heads are mostly above water now, instead of always feeling like we're drowning. Time is set aside each week to discuss the "what ifs" and "what could happen" and even if we don't get to a solution or even a plan, the team has collaborated, and all are on the same page with identification of potential "Bangs."

2. Predictability. Often my team would refer to adverse events (BANGS) as "the perfect storm." Because of this rationale we would pity ourselves and our situation putting it off to the side as something we couldn't control. With Left of the Bang, we dig! We do not allow ourselves to be the "victim" and have realized than many of those events could have/should have been prevented with proper preparedness. We find ourselves asking better questions of each other such as "Should we have known this event would occur?" "What pre-event indicators existed?" and "Why didn't we see those indicators?" No more pity parties for us!

3. Training and Skills. Equipping healthcare workers with the right tools is vital. Situational awareness has become a key concept in our orientation and all our annual training and competencies. Identifying a change in condition is one of the most important skills a nursing home nurse or CNA must possess, using Left of the Bang we now talk in terms of baselines, deviations and patterns. Even a simple word shift has boosted our awareness and critical thinking. These concepts have reshaped my role in Learning and Development and put a new spin on required annual training regulations that staff dread each year.

The sky's the limit when applying the Left of the Bang concepts to Skilled Nursing. Stumbling upon your book has taken my career and life in a completely different direction and re-ignited a lost fire I once had. As a mom of two teenagers, these concepts have become routine discussion in our home. When we're at the movie theater and my 14 year old daughter points out a hidden exit she would go to in case of an emergency, I just smile! There's no better feeling for a mother, than peace of mind that her kids have the right tools to be safe.