When Awareness Becomes an Advantage

Designing Situational Awareness to Get Left of Bang

Introduction

Every serious attempt to get left of bang rises or falls on situational awareness. There is no workaround to the fact that, if you don’t understand what is unfolding around you well enough to recognize it early, you lose the opportunity to get in front of it.

The problem is that situational awareness is often treated as a general posture rather than a specific capability. People are told to “be aware” without any clarity about what they are trying to recognize, how they will know it matters, or what they will do differently when they see it taking shape. In that form, awareness becomes passive because observations are collected, yet rarely lead anywhere. Those observations just become part of a story told afterward about how—in hindsight—it was all visible.

Getting left of bang requires something more deliberate and informed. Awareness has to be oriented toward recognition, tied to assessment, and connected to decisions that can be made before time runs out. Without any of those chain links in place, even early signals fail to create an advantage.

The Problem With “Being Aware”

Situational awareness is not sitting with your back to the wall, keeping your phone in your pocket, or keeping your head on a swivel. Those are habits.

The same thing shows up in organizations where teams diligently read intelligence briefings, industry reports, and situational assessments. The information may be reviewed, discussed, and circulated, but none of that, by itself, constitutes situational awareness.

These habits may allow you to see things, but seeing is just sensory. They don’t determine whether someone actually understands what they are looking at, whether what they are noticing matters, or what they should do with it once they’ve noticed it.

Awareness, on the other hand, requires recognition, and recognition is interpretive. It requires making sense of what you are seeing in the context of what you are responsible for, and deciding whether it deserves attention beyond the moment it was observed.

This is why telling people to “look for anything suspicious” almost guarantees they will miss what actually matters. Without a clear focus, attention naturally drifts toward the obvious, the unusual, or the alarming. Meanwhile, quieter and more meaningful indicators are rationalized away, dismissed as inconclusive, or simply ignored because they don’t demand immediate action.

For observation to become awareness that can support confident, proactive decisions, the observer must be clear on three things:

What, specifically, they are looking for.

How they are going to look for those indicators and make sense of what they find.

What they are prepared to do once something meets the threshold for concern.

Someone who can answer those questions is not passively monitoring their environment or hoping something catches their attention. They are deliberate and directed. Their observation has a purpose, and their attention is oriented toward decisions, not just detection.

This is also what prevents awareness from breaking down at the organizational level. When people are clear on what they are looking for, how they will recognize it, and what they are prepared to do next, information stops drifting through the system without settling anywhere. Camera feeds, reports, briefings, and updates stop being something people simply acknowledge and move past. They become inputs tied to specific decisions and owned by specific people.

Instead of information circulating endlessly—everyone nodding, adding context, and offering perspective without consequence—it begins to accumulate in a way that leads somewhere. Recognition has a definition, and decisions have an owner. Observation no longer fades out of the conversation, because it is connected to an agreed-upon threshold for action.

Without that structure, situational awareness never becomes a decision advantage—it just becomes an explanation offered after the fact.

Recognizing What Matters

Once awareness is tied to decisions, a hard but necessary question follows:

What, exactly, are you trying to become aware of?

First, I’ll acknowledge that there is no universal answer to that question. It is field-specific, role-specific, and responsibility-specific.

But taking ownership of the question starts with clarity around decisions. What decisions are you responsible for making? What outcomes will you be held accountable for? Those questions define what matters enough to monitor in the first place.

A security team may be focused on identifying credible threats.

A communications team may be monitoring for emerging issues that could erode trust or credibility if left unaddressed.

An emergency manager may be watching for changing conditions that signal increasing hazard or operational strain.

An operations center may be focused on unusual patterns of supply, demand, or system stress.

A business executive may be looking for unmet needs or recurring friction points that suggest a shift in customer expectations.

Once the condition or event you care about is defined, awareness can move from vague vigilance to something concrete. You can begin identifying the pre-event indicators that suggest that the condition is developing, even if it is not yet obvious or fully formed.

In threat recognition, those indicators may be behavioral cues that distinguish legitimate presence from violent intent.

In emergency management, they may take the form of Watch Points or Action Points that precede a disaster.

In business settings, they may show up as recurring questions, complaints, or requests that point to something more than a one-off issue.

Defining pre-event indicators is important because it turns awareness into something tangible. If indicators can be articulated, discussed, trained, and shared, then recognition stops being an individual trait and starts becoming a capability that can be built and maintained across a team or organization.

But establishing indicators is only part of the work. On its own, a single indicator rarely carries enough weight to justify action, which means awareness also has to account for how indicators accumulate and combine. This is why effective awareness also includes an explicit threshold for decision-making.

In the Tactical Analysis Course, which draws heavily on lessons from the Marine Corps’ Combat Hunter Program, this is taught as the “Rule of 3s.” When three relevant cues are present, a decision is required—even if certainty is still incomplete. The rule is not about counting for its own sake, but is built to prevent endless observation from creeping into the time available for early action.

Sometimes, though, what you notice will introduce more doubt and questions than you are ready to answer through observation alone. In those cases, awareness has to be paired with an assessment process—one that allows you to validate, disconfirm, or better understand what you are seeing before committing to action. Extending the observation process to include an assessment process helps prevent people from over-reacting to weak signals or under-reacting to meaningful ones.

This is the work that allows awareness to create advantage. Without recognition, thresholds, and assessment, early signals remain observations. With them in place, awareness becomes the mechanism that creates time, options, and the ability to get left of bang.

From Awareness to Action

Developing informed situational awareness only creates value if it can be applied. Understanding what is happening, recognizing early signals, and assessing despite ambiguity all buy time—but time only matters if it is used.

This is why any serious conversation about situational awareness eventually has to include Cooper’s Color Code, and more specifically, the ability to operate effectively in Condition Orange.

A Snapshot of Cooper’s Color Code

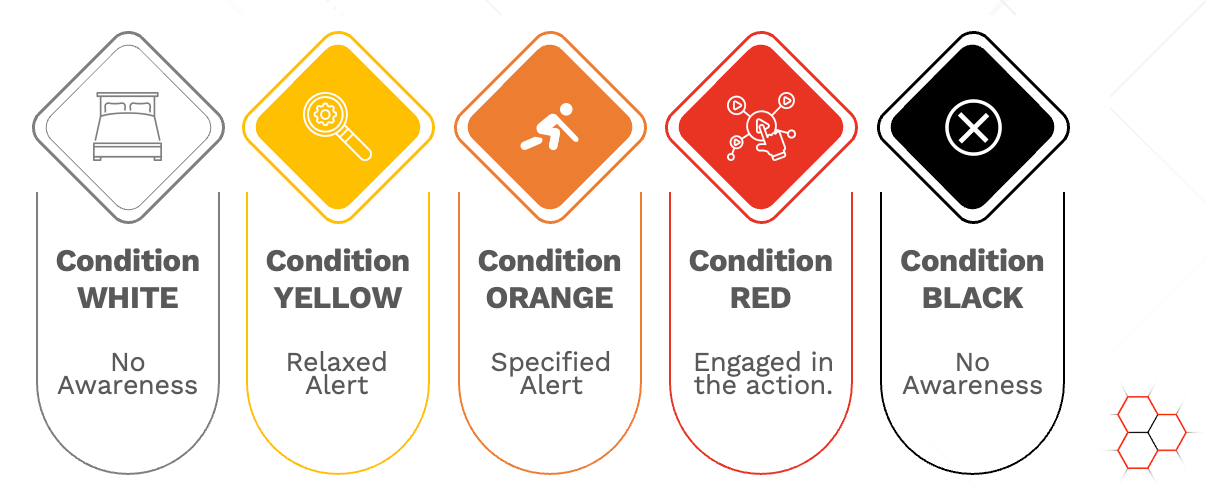

Cooper’s Color Code offers a way to describe situational awareness and, more importantly, a person’s readiness to act.

Conditions White and Black represent a person who has no situational awareness.

Condition Yellow is a person who is actively scanning their surroundings for potential threats or opportunities, but has not identified anything specific that warrants future focused attention.

Condition Orange is the state a person enters when something has attracted their attention and they begin forming a plan for how they might deal with it.

Condition Red represents a person who has begun implementing their plan.

For a deeper explanation, here is an article that applies the concept to severe weather readiness.

Condition Orange is emphasized because it functions as the left-of-bang hinge. It is the point where awareness either converts into action or stalls out. This is where a person or organization pivots from intentionally searching for pre-event indicators into making decisions that shape what happens next.

A ready person or organization is able to enter Condition Orange deliberately when they have an intentional process for recognizing pre-event indicators repeatedly, under pressure, and without hesitation. But Condition Orange only creates opportunity—it does not resolve it or determine how that time is used. A decision still has to be made.

This is where preparation shows. There is a meaningful difference between telling people to “look for suspicious things” and establishing expectations that say, “if we see X, we do Y.” In environments defined by limited time and incomplete information, hesitation is often indistinguishable from inaction. Awareness that is not paired with a decision path rarely changes outcomes.

When inputs are tied to pre-planned responses, every minute gained through early recognition can be used deliberately rather than consumed by debate. Recognition leads to assessment, assessment leads to a decision, and the decision leads to action while options still exist.

Organizations that struggle here tend to fail in predictable ways. Some never truly enter Condition Orange at all, instead remaining in a state of generalized awareness, waiting for information to become clearer on its own. Others recognize that something is developing but have not thought through what decisions should follow, leaving them stuck in a prolonged state of focused attention with no forward movement. In both cases, early signals are seen, time is created, and the opportunity quietly closes.

A dialed-in approach to Condition Orange is what readiness looks like in practice. It is not constant vigilance or perfect information. It is the ability to move from awareness to action deliberately, using the time created by early recognition to shape outcomes instead of explaining them after the fact.

In Closing

Organizations and individuals cannot care about everything. Time, attention, staffing, and resources are finite, whether we acknowledge that openly or not. That means that the people and organizations able to elevate situational awareness to a level that is actually useful are able to prioritize.

Trying to watch everything spreads attention so thin that nothing is monitored well.

This makes the starting point deciding what truly matters. What are the mission-critical risks, threats, hazards, or opportunities you will be held accountable for? Not everything that could happen or everything that feels important. The things that, if missed, would force decisions on you later under worse conditions.

Ultimately, situational awareness is about knowing what you care about, defining what to look for, how you interpret what you see, and what you are prepared to do with it. That is what allows teams to stop passively waiting for information to arrive and start hunting for the signals that matter.

That shift—from information hoping to information hunting—is what creates the opportunity to act earlier, use time deliberately, and get left of bang.

Enjoyed This Article? Pass It On.

If this article sparked ideas, share it with your network, a colleague, or on social media. Sharing is how we expand the community of professionals committed to staying left of bang.

I like the part about knowing what you are accountable for...that really gives context to what my action plan is...very different if your a dad with family downtown ....LE or military on duty.

Great read - we focus so much on information gathering, without asking "okay, now what?". We're working through that in our EOC - why are we gathering this and what are we delivering with it? What is our value-add to this situation?